Project Spotlight: NOAA KAMERA

Kitware’s field work can take many forms, but it’s not every day we get to venture out into the Arctic Circle within eyeshot of Siberia. Our team participated in an extensive system testing and integration event in Nome, Alaska to help the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) prepare for a massive seal survey in 2025.

About NOAA

NOAA is a U.S. scientific and regulatory agency charged with forecasting weather, monitoring oceanic and atmospheric conditions, charting the seas, conducting deep-sea exploration, and managing fishing and protection of marine mammals and endangered species in the U.S. For the KAMERA project, we were funded and directed by NOAA Fisheries, working directly with their Polar Ecosystems Program, tasked with researching and monitoring the population and distribution of seals in the Arctic and sub-Arctic marine ecosystems. Their focus species include harbor seals and ice-associated seals: bearded, ringed, spotted, and ribbon seals in Alaska. In partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the project also includes polar bears in its surveys. Indigenous Alaskan communities greatly rely on these species, but due to their expansive distributions and remote habitat, their populations are not well understood.

The Challenge

The existing method for monitoring these mammals involves flying a crewed aircraft over the frozen seas surrounding Alaska to capture hundreds of thousands of images. Traditionally, these images were often unsynchronized, stored across multiple devices, and laboriously reviewed and meticulously annotated by hand after running coarse detection algorithms to help find animals in the imagery. This process is error-prone and the results can be delayed by years. Given that this data impacts policy decisions on the preservation of these animals, a more efficient and cost-effective approach is essential.

KAMERA: Kitware’s Edge Computing Solution

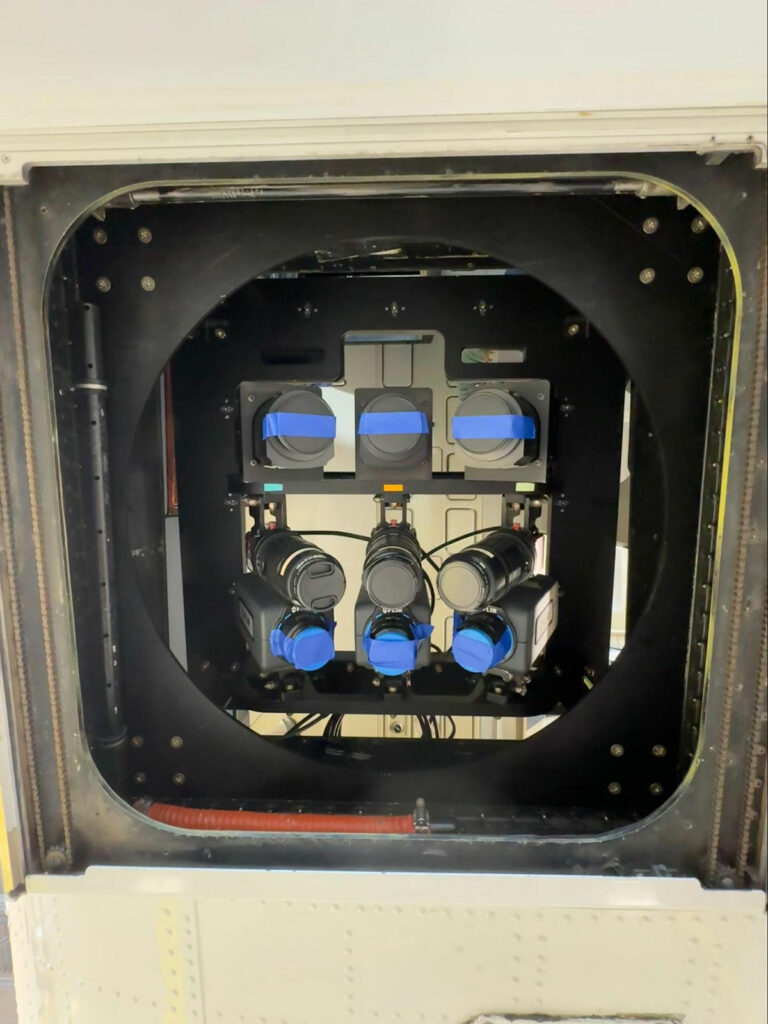

Starting in 2018, Kitware began developing the Kitware Image Acquisition ManagER and Archiver (KAMERA) system. This system comprises 9 cameras covering 3 image modalities– Ultraviolet (UV), Infrared (IR), and Color. They were designed to be tightly synchronized and provide a robust solution for detecting mammals, collecting imagery, and mapping them over the survey area. The hardware includes rugged compute systems with a GPU for real-time deep learning. We leveraged our expertise in deep learning and used VIAME, Kitware’s open source do-it-yourself deep learning toolkit, and AI models from the University of Washington for real-time seal and polar bear detection.

(Left) The 9-camera system installed in the belly of the aircraft. On top, the 3 color cameras, in the middle, the 3 UV cameras, and the 3 IR cameras on bottom. This configuration captures a wide swath of imagery in flight, maximizing area covered.

(Right) During assembly, routing cameras to the compute systems. The 3 blue boxes in the rack are the compute systems, and the black square in the floor contains the camera rig. A pressure dome is placed over this opening so the aircraft can be pressurized and flown up to 35,000′.

KAMERA is an edge computing solution designed to address several critical issues:

- Synchronization: Ensuring that all 9 cameras are tightly synchronized to capture images at the exact same moment, which is crucial for associating between modalities (i.e., IR hotspots to Color imagery).

- Association: In addition to synchronizing between images, knowing the exact time and place via an Inertial Navigation System (INS) is needed for accurate geospatial mapping, so we can place these detections in the real-world.

- Real-time Processing: Using ruggedized compute systems with GPUs to process images in real-time allows for immediate detection and analysis of marine mammals, and enables images to be discarded in-flight, speeding up survey results afterwards.

- Robustness: The system needed to be durable enough to withstand the harsh conditions of the Arctic and be easy-to-use since its operators would be unfamiliar with this type of technology.

An Open Source Solution

Kitware has been a proponent of open science since our inception, and as a civilian science agency NOAA has a charter to make its data and software available to the public. In line with this, all of the software we designed and deployed for KAMERA is open source and available on Github.

Deployment and Field Testing

The KAMERA system was shipped to NOAA and used in 2021 for a full survey of the Beaufort Sea on the North Slope of Alaska, collecting over 900,000 triplets of imagery. In 2022, we created a smaller version for an uncrewed aerial system, flown around Shemya Island on a NASA Sierra B drone at the edge of the Bering Sea in 2023. All this work was in preparation for a monumental survey that will take place in the Spring of 2025, covering the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas collectively.

During the 2021 survey, the system demonstrated its capability to handle the harsh Arctic conditions, capturing synchronized images across multiple modalities. This allowed for more accurate detection and mapping of marine mammals, significantly improving the efficiency of data collection and analysis.

In the last year, we upgraded the compute systems to modern architectures, the color cameras to massive Phase One cameras, and made numerous software upgrades to support these platforms. This culminated in our most recent flight tests in June 2024 in Nome, AK, where Kitware’s team participated in testing and integrating the system. Not only was the whole system upgraded, but we also tested the system in a new plane, NOAA’s long-range King Air, to enable farther and faster survey efforts next year.

Results and Impact

The 9-day field test in Nome was a pivotal experience, providing invaluable insights into the mission and hands-on engagement with the system and the NOAA team. This was the first opportunity the team had to fly with the upgraded system, with eight flights over the Bering and Chukchi seas, each lasting about four hours. The upgrades performed well, and we observed how the new plane would handle the system in the Alaskan winds. This successful trip to Alaska gives us confidence in our solution for the upcoming massive survey efforts next year. We presented our work at STRATUS 2024, a UAS conference in Syracuse, New York (contact us if you would like us to send you the slides). Kitware is excited to see this system continue to improve and expand to support other environmental monitoring efforts.

Looking Ahead

As we prepare for the extensive surveys in 2025, we are focused on continuous improvement and innovation. The data collected will not only provide critical insights into the populations of marine mammals but also influence policy decisions that impact conservation efforts. Kitware is excited about our continuous collaboration with NOAA, and this opportunity to solve real-world challenges through edge computing technology that will help protect our planet’s vital ecosystems.

For more information about Kitware’s edge computing capabilities or the technology mentioned in this article, please contact our computer vision team.

Feature image caption: Adam Romlein and other members of the NOAA team posing at the Nome, AK welcome sign.

Great stuff! Are you thinking about how this would scale to(or are similar systems already in use for) other environmental use cases? E.g. other species?

Thanks for the question! We’re definitely looking into how we can support other groups within NOAA and elsewhere with either this system or a variant of it. We’ve talked with whale monitoring and sea turtle monitoring groups, and they’ve both been really interested in using our system.

There are certainly commercial solutions out there that solve the sensing art of this problem – large camera racks with compute systems attached for in-flight collection. But there are very few that implement the real-time deep learning aspect of our project, taking this cutting-edge research and creating a bespoke system, and then actually putting it onboard a plane.

How many species of seals (and how many mammals in total) did you manage to find during your venture to the artic circle? Is the hardware capable of picking up mammals right below the surface of Alaskan waters (if so, to what depth)? Also, from all the field tests done so far, how robust would you say the different cam modalities are at capturing from different flight heights and during different lighting based on the weather (or even at night)? Thank you!

Thanks for the questions! Sorry for the late reply… This journey was specifically for system integration and testing in preparation for the “real” 2025 survey, so we didn’t get an exact count of the mammals. I know we did see ribbon and ringed seals, walruses, and some whales! You can see our pre-trip brief here: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/s3//2024-05/research-brief-2024-iceseals-aerial.pdf.

We can’t pickup any mammals under the water, which is why our survey period is so limited to the 4-6 week period in the Spring when the sea ice is breaking up, and the seals come up to molt and raise their pups.

The color and infrared modalities are fantastic at our survey height of 1000ft. The color cameras would be able to image at a higher altitude, but since the infrared cameras are at a much lower resolution, seal hotspots start to collapse quickly to a handful of pixels. Our UV modality is not great at the 1000ft altitude, and its only real purpose currently is to help pick out polar bears by eye. We’re looking at how we can train models on it though. We have never run the system at night, and if there is cloud cover below 1000ft we can’t survey either. Hope that answers your questions!